Mr. Bennet is a Terrible Dad

Amiable film portrayals notwithstanding (RIP Donald Sutherland!), the book character is not meant to be emulated.

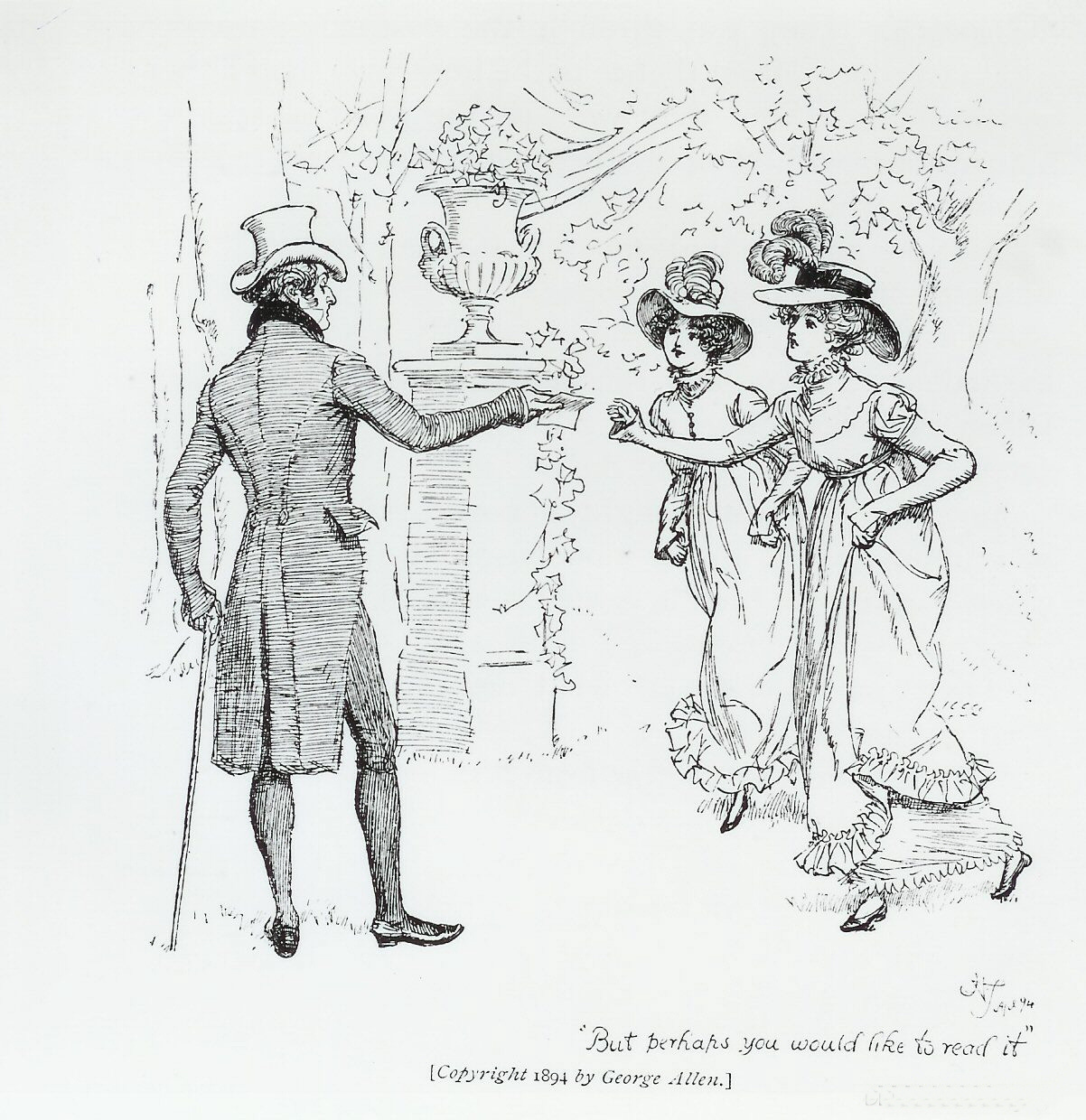

Happy Father’s Day a week late! Let’s talk about how Mr. Bennet of Pride and Prejudice is not a role model for parental figures. Or any figures, even those shown to best advantage during a turn about the room at Netherfield.

Yes, this is a picture of Donald Sutherland as Mr. Bennet in the 2005 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice (P&P). It is no secret that I do not care for this film. I have nothing against Donald Sutherland as an actor— indeed, the same may be said for most of the talented cast—but the character he portrayed (and portrayed well!) was not the Mr. Bennet of the book. And in the wake of Donald Sutherland’s passing, my admittedly Austen-biased social media feeds have exploded with fond tributes to his portrayal of Mr. Bennet.

Except, unfortunately , Mr. Bennet sucks. Here’s why, in no particular order.

He is selfish and indolent, more interested in his man cave than his daughters.

Mr. Bennet can usually be found in his library— “not to be disturbed” as he says in the 1995 miniseries. What is he doing in there, exactly? Just reading, it turns out. He is not conducting business, nor writing anything of value, nor making provisions for his family in the event of his death (whereupon they will be unceremoniously kicked out of Longbourn estate so Mr. Collins can set up beekeeping, or grow rutabagas, or breed llamas, or do whatever strikes his fancy and garners the approval of the noble Lady Catherine de Bourgh).

Listen, I am all for reading. I have heard it said that extensive reading improves a lady’s mind, and one can hope it might be prevailed upon to do the same for a gentleman (privileged and self-centered as he may be). But it has not improved upon Mr. Bennet’s talents as a father. He spends little to no time with his children, has not cared enough about their upbringing to secure a good governess for them (or to ensure that his wife does so), calls them “silly and ignorant, like other girls” (chapter 1) and is only driven to stir his rear end out of his winged armchair to go call on Mr. Bingley with the incentive of being able to troll his wife about said call. Which brings me to…

He mocks Mrs. Bennet in front of their children. Not cool.

Look, a teasing relationship is all well and good. I feel quite certain Darcy and Lizzy will have that! (More on them later.) But the fun Mr. Bennet has at Mrs. Bennet’s expense is not mutual. She is annoying, to be sure. But he also chose to marry her. He was blinded by a pretty face in his youth and made a hasty choice (which he had far more agency to make than she did, by the way!) and now they’ve been stuck together over 20 years, but them’s the breaks in a patriarchal society, Mr. B. You’ve buttered your bread, now lie in it.

He has made no worldly provision for his daughters despite having at least fifteen years to get his act together.

We are not talking about some sort of Bronson Alcott type who believes God has called him to the ascetic life and he’s going to raise his family in dire poverty and live on fruit and seeds. No. Mr. Bennet has a nice house with a nice library in a nice neighborhood and yet he is fully aware that when he kicks the bucket, Collins the clergyman and his bees (maybe rutabagas, llamas, and Lady Catherine) will zoom in and take his place. Mr. Bennet has five daughters who by British entailment law, which I do not pretend to understand and will not waste time attempting to explain, cannot inherit the Longbourn estate because they do not wear breeches. Great system. Totally fair for everyone. Jane Austen was definitely saying this was a good idea and everyone should keep doing it.

/sarcasm

(You have to insert these disclaimers on the internet these days. The AI-ification of the world wide web is destroying reading comprehension, I do believe.)

Now, if the Bennets had had a son, the responsibility of caring for his mother and many sisters would have fallen to that guy. (Let us hope he would not have been another John Dashwood.) But they didn't! Lydia, their last baby, is fifteen going on sixteen (not exactly innocent as a rose). Mr. Bennet has had a decade and a half to get used to the idea that his girls are going to be destitute, and he has done diddly-squat about it.

He makes no attempt to corral the behavior of his younger daughters when it matters, and only steps in where no material benefit can be gained

Lydia’s wild behavior, raucous obnoxiousness, and underage drinking get a pass, but Mary sitting down at the Netherfield pianoforte is what prompts the Father Knows Best remonstrance? My good sir. Priorities.

Elizabeth is openly Mr. Bennet’s favorite, and Jane never seems to garner any of his snarky remarks, and Lydia and Kitty completely ignore his quips, but poor Mary is the one he chooses to blatantly make fun of. “What say you, Mary?” he teases her, “For you are a young lady of deep reflection, I know, and read great books and make extracts.” (chapter 2) Heaven forbid Mr. Bennet appreciate that one of his daughters wants to read big books and be a bluestocking! Heaven forbid he actually throw her a crumb of approval. And when Mary “obliges” the company by playing and singing at the Netherfield ball, heaven forbid he just let her do her thing. (To be fair, Elizabeth is the one who urges her father to stop Mary. But then she feels bad, because Elizabeth has a conscience and a sense of justice.)

Mary's powers were by no means fitted for such a display: her voice was weak, and her manner affected. -- Elizabeth was in agonies. She looked at Jane, to see how she bore it; but Jane was very composedly talking to Bingley. She looked at his two sisters, and saw them making signs of derision at each other, and at Darcy, who continued, however, impenetrably grave. She looked at her father to entreat his interference, lest Mary should be singing all night. He took the hint, and when Mary had finished her second song, said aloud, "That will do extremely well, child. You have delighted us long enough. Let the other young ladies have time to exhibit."

Mary, though pretending not to hear, was somewhat disconcerted; and Elizabeth, sorry for her, and sorry for her father's speech, was afraid her anxiety had done no good. Others of the party were now applied to. (chapter 18)

And, of course, when Lydia goes off to Brighton, Mr. Bennet makes no objection. When Elizabeth “represents to him all the improprieties” of Lydia’s behavior in public, Mr. Bennet shrugs off her concerns. “Lydia will never be easy till she has exposed herself in some public place or other,” he says, “and we can never expect her to do it with so little expense or inconvenience to her family as under the present circumstances.” (chapter 41) A great point! Gotta save that money to buy more books for the dude den which Mr. Collins can then throw away to make more space for the collectors’ editions of Fordyce’s Sermons. Good plan. No notes.

/sarcasm again

Mr. Bennet’s comeuppance near the end of the novel does not redeem his bad qualities throughout.

Yes, when Lydia runs away with Wickham, Mr. Bennet is somewhat abashed. He can’t resist getting in a few digs at his wife’s dramatic misery, of course (“It gives such an elegance to misfortune! Another day I will do the same: I will sit in my library, in my nightcap and powdering gown, and give as much trouble as I can”) but he admits he was wrong to not have protected Lydia. “Who should suffer but myself? It has been my own doing, and I ought to feel it,” he tells Elizabeth (chapter 48).

But Mr. Bennet is not the one who ultimately finds Lydia, nor the one who pays Wickham off to make her “respectable,” nor the one who presses Aunt Gardiner for details on how it all came about. (He could have asked. I’m just saying. He chose to chill instead.) And though in the 1995 miniseries he says, “I’m heartily ashamed of myself, Lizzy. But don’t despair, it will pass... and no doubt more quickly than it should,” (episode 6) no such self-awareness is present in the novel. Indeed, as Lydia and Wickham return to Longbourn as a married couple, he merely gives them the silent treatment at first, allows himself one eye roll at a particularly indecorous remark of Lydia’s, and then dryly remarks upon Wickham’s “simpers and smirks” (chapter 53) as the dubiously happy couple departs.

I said I was going to do this in no particular order, but this last one is the kicker and that’s why I saved it:

Jane Austen doesn’t want us to like Mr. Bennet. He isn’t meant to be anyone’s favorite.

Austen’s characters are not two-dimensional caricatures. Mr. Bennet is neither mere comic relief nor a beleaguered, well-meaning old man. He is funny, to be sure, and he has a ready wit and a decent appreciation for his cleverest daughter. But he is also all the things I listed above.

In satirizing polite society as she did so deftly in P&P, Jane Austen gave us a portrait of a man who is more complex than he seems on the surface. She also let us see him both through the fretful eyes of his wife (so trying to her poor nerves!) and through the benevolent eyes of his favorite child (“I could not have parted with you, my Lizzy, to any one less worthy” he says upon hearing of Mr. Darcy’s proposal in chapter 59. Jane pretty much just gets a pat on the head). Elizabeth is eager for her father’s approval and amused by his “diversions,” but please remember that Elizabeth is not exactly a model of accurate intuition and good character judgment. (Let me present exhibit A: Mr. Wickham. Let me present exhibit B: Mr. Darcy.)

Elizabeth is prejudiced in favor of Mr. Bennet because in many ways she is a lot like him. She has a quick wit, a sharp tongue, and a tendency to “delight in anything ridiculous.” But Elizabeth grows and matures throughout the novel, and Mr. Bennet falls back into his old ways of sarcasm and solitude as soon as the wedding bells chime. Mr. Bennet’s head was turned by a pretty face, and he married without respect or affection; Elizabeth, whose fine eyes caught the attention of a good man who had (still has!) his own maturing to do, married someone she can appreciate as an equal. Teasing and laughing as their relationship may be, Elizabeth and Darcy will ultimately be very happy.

Don’t be a Mr. Bennet, Jane Austen is telling us. He has only his books for comfort. His mind—his understanding, his affections, his perception of human nature—have not been improved by his extensive reading. He lives only to make sport for his neighbors, and to laugh at them in his turn.

Elizabeth Bennet—and you—deserve better.

Okay, your turn! Tell me what I missed about Mr. Bennet. Do you feel he deserves a second chance? Or is he even worse than I have made him out to be? Leave a comment and I will read and respond with pleasure! If you choose to share this post on social media, I shall be excessively gratified. (Do tag me, please, so I can respond!)

This post is a part of The Summer of Jane Austen, a literary-inspired endeavor that will (I hope) fuel both a journey of the mind and my own journey to the Jane Austen Society of North America’s Annual General Meeting. More here.

Love this reflection!

I think it's really powerful that the first person we hear disparage Mr Bennett is Mr Darcy. Up to that point we have enjoyed him so much as a character, and adored him a little because of Elizabeth's bias. Now we see him from a cold, outside perspective. Like Elizabeth we maybe aren't ready to hear the critique. But now our eyes are open for the rest of the book.

I'd not realized that the 1995 line about "it will pass, no doubt more speedily than it should" was an addition, it's such a good one that absolutely captures Mr. Bennet!

I remember a talking head saying once that Mr. Bennet was the most like Austen herself out of all her characters--holding himself apart from everyone else and just making droll, wry observations. I'm not sure this is entirely fair to Jane, perhaps he is simply what she feared she might become if she indulged her worst tendencies.

I do think one recurring secondary theme both of the book itself and some of my favourite reinterpretations of it (including, most recently, The Other Bennet Sister by Janice Hadlow) is learning the difference between a sort of caustic wit that holds itself apart from all or most others, and wit that is tempered with kindness. The former is obviously bad for the targets of the caustic wit, but also for the wisecrackers themselves, who lose out on the better relationships they might have if they learned to look for the best in people.