How a Forgotten British Princess Became a Silent Film Star and Invented the Band-Aid

History forgot her, but her legacy lives on… in drama and adhesive bandages.

Queen Victoria of the British Empire and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha had nine children together. Their seventh child, Princess Alexandrina, was destined for greatness. Born on October 10th, 1852, she lived to be nearly 80 and led one of the most fascinating lives a titled noble could hope to claim.

As a small girl, Alexandrina took an interest in medicine, writing elaborate entries in her journals about her observations of the court doctor, but of course a career in medicine was out of the question for a princess of the British Empire.

Prince Harry was not the first British royal to wed an American commoner. In 1880, at the astonishingly advanced age of 28, Princess Alexandrina married Horace Dinsmore, owner of a stewed-fruit cannery in South Carolina and heir to a massive cotton fortune. Queen Victoria, a long-time critic of the erstwhile slave trade in the American South, approved the match but was dubious about the source of Dinsmore’s fortune. Her famous diary entry decrying “blood money" is thought by many scholars to be a veiled reference to her son-in-law’s wealth. However, Victoria wrote on her daughter’s wedding day,

Words cannot express the joy I feel at seeing my most difficult daughter at last united to a man who will bring her all the happiness and domestic felicity which I erstwhile enjoyed with my beloved Albert.

(A “fun fact" mostly unrelated to this history — actress Emily Blunt, who would go on to play Queen Victoria in the 2009 feature film, is a direct descendant, through her American grandfather, of Horace Dinsmore’s sister Adelaide.)

The couple settled in South Carolina in a modest 70-room mansion near Charleston, but their happiness lasted only briefly, for after four years of marriage Horace ran away with Rose Allison, a neighboring widow, and the scandal that ensued cannot be overstated.

Queen Victoria, though famously stoic as regarded her children, displayed rare emotion in begging Alexandrina to return to England and take up residence again in Buckingham Palace, where she would be shielded from a prying press. But Alexandrina was not interested in going back to her old life in England. “My dear daughter refuses to return to her homeland and take refuge with her beloved family,” Victoria wrote in 1884. “As for my part, I always disliked the American rogue, and his name shall not cross my lips again.”

For the next decade, Alexandrina stubbornly remained in the United States, circling through the homes of her society friends in South Carolina. In 1895, she joined Evelyn Ashcombe, the widowed daughter of her friend Martha Vanderbilt, and moved to New York City.

Little is known about the period of time between Alexandrina’s trip North and her “rebranding” in 1911. Her letters from those years were burned shortly before her death. But in 1911, after what historians can only conclude must have been an adventurous time of socializing with artists and thespians, Alexandrina’s letters to her most intimate friends reveal that she had changed her name to Nelly Forsythe and had begun to appear in silent films.

Young actresses such as Mary Pickford and Pearl White were charming the hearts of moviegoing Americans as the beautiful heroines of melodramatic adventures, but every swooning starlet needed an elderly mother, housekeeper, or school headmistress as the down-to-earth antidote of her box office perils. “Nelly Forsythe,” in her own way, captivated nearly as many hearts as “America’s Sweetheart” Mary Pickford.

By 1918, “Nelly Forsythe” was romantically involved with a French doctor, Edouard Versaille, who escorted her to her film premieres and called weekly at her magnificent Manhattan home. Alexandrina’s girlhood dreams of practicing medicine were never fully realized (though her role as Mother Evelina, head nurse of a Civil War field hospital, in the 1919 epic The Spoils of War, garnered much acclaim) but she left her mark on the healing profession nevertheless. In 1920, with the support of her physician “gentleman friend,” she filed a patent for the adhesive bandage she had fashioned for her beau’s pediatric patients.

The Band-Aid, as it soon became known, was quickly rolled out on the manufacturing lines of Johnson & Johnson pharmaceuticals. News of Horace Dinsmore’s death reached New York in 1922, and before that year was out, “Nelly” and Edouard were married in a quiet ceremony near her Staten Island film set.

In the Roaring 20’s, most film production had moved from New York and New Jersey to the more agreeable weather of Los Angeles, California. Alexandrina appeared in her last film, a “talkie” adaptation of Jane Eyre, as the elderly Mrs. Fairfax in 1925. Even at the age of 73, she had not lost her cultured English accent, and her part in the movie was met with positive reviews.

Alexandrina Maria Louisa, Duchess of Albany, alias Nelly Forsythe Versaille, died peacefully in her sleep on May 1, 1930. Her beloved husband Edouard followed her six months later.

Her story has nearly been forgotten, but her most ingenious creation lives on as an everyday remedy for cuts and scrapes.

Now, what if I told you that none of the above is true?

That’s right, none of this happened.

I made up almost every word of it.

If you go back to the beginning and check, you will find… not one single citation for any of these facts.

Any reputable writer of history will provide sources for the information they share, and I have just written the most disreputable “history” I can ever hope to claim.

Here is what is real:

Victoria and Albert had nine children. (None of them were named Alexandrina, though Alexandrina was actually Victoria’s first given name.)

Emily Blunt played Queen Victoria in The Young Victoria.

The Band-Aid was invented in 1920.

That’s it.

The rest is from my imagination. (The name Horace Dinsmore comes from a particularly loathsome series of 19th-century children’s books.)

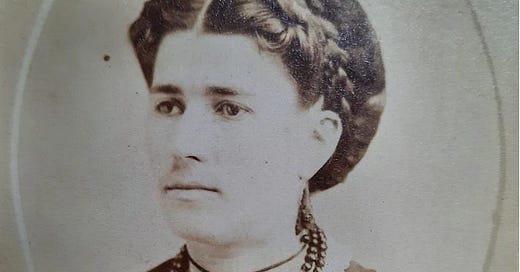

The photo at the top is an unknown woman photographed in the late 1870s; it’s part of my private collection.

I had a lot of fun making up the history you just read, but I wrote this to prove a point, not just to flex my fiction muscle.

I am appalled at the number of history pieces I come across — particularly on this platform — that set out to tell an interesting story, yet fail to tell the reader where they got all the information. Why should an intelligent reader, exploring your writing for the sake of learning, believe anything you have to say if you don’t back up the statements you make?

I beg you: if you’re writing a story of What Happened, let me know that your Happenings are credible.

We live in a world of misinformation and poorly shared information. “I read it on the Internet, so it must be true.” But these days, I’ve been telling myself “if I read it on the Internet, it’s not true until I’ve fact-checked it.”

The internet is full of articles purporting to teach you things you didn’t learn in school. Read the ones that cite their sources.

And also… don’t comment on anything until you’ve read all the way to the end.

I SHRIEKED when I got to Horace Dinsmore--truly loathsome books! My Elsie doll was pretty, though; I quite liked her ringlets.